Three years after Vladimir Putin launched his full-scale invasion, Ukraine still faces a very uncertain future.

Just one month after Donald Trump’s return to the White House, the US president has thrown whatever hopes Kyiv had for future American support into chaos.

In the last week alone he has launched repeated attacks on Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelensky, falsely branding him a “dictator” and wrongly accusing Ukraine of “starting” the war.

And so Ukraine now finds itself fighting a war on two fronts: the grind against the Russian invaders to the east, and the battle to keep Mr Trump on side to the west.

Here, The Independent looks at the very real costs of three years of war in Europe – financially, militarily and on the lives of the men and women who continue to fight for their freedom.

The human cost in civilians and soldiers

In active wartime, it is difficult to accurately gauge the numbers of people who have died on either side.

Conflict specialist non-profit ACLED (Armed Conflict Location and Event Data) estimates there have been around 153,000 Ukrainian and Russian casualties since the war began on 24 February 2022, based on over 140,000 individual news-reported events.

The UN Human Rights Office (OCHR) puts the number of civilian deaths at around 12,654, including at least 669 children. The UN says there have also been more than 29,000 civilians injured. Civilian casualties have increased by 30 per cent in the past year as a result of increased drone strikes, it adds.

An estimated 20,000 children have been abducted into Russia or Russian-occupied territory since the start of 2022, separated from their families and country. An investigation by The Independent suggests that Ukrainian children have been sent to dozens of re-education camps, where behaviour is abusive and children sleep with barred windows.

Earlier this month, Kyiv estimated the number of Ukrainian soldiers killed topped 45,000, with 380,000 wounded and tens of thousands more missing in action.

Russia has not provided figures on the number of soldiers who have died. A collaboration between BBC Russia and Mediazona identified the names of over 90,000 Russian soldiers who they estimate to have been killed, as of January this year. The Ukraine Armed Forces claim a far higher number, suggesting around 854,000 Russian casualties.

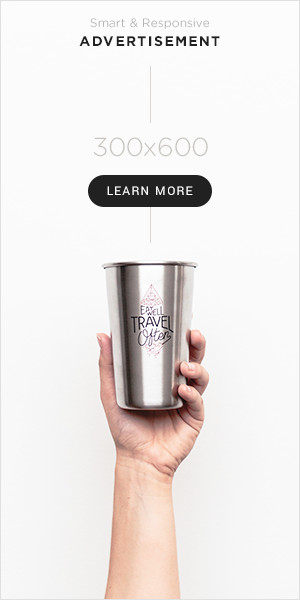

The refugee crisis as millions displaced

Millions of people fled the country in the first months of the war, through Poland, Romania and Moldova into Europe and beyond.

Three years later, millions of Ukrainians are still far from their home country and many without homes of their own.

According to the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR), there are currently over 6,906,000 Ukrainian refugees recorded globally.

“We must not forget, that the war still continues every single day, with large-scale attacks, more killings of civilians, destruction of homes and critical infrastructure and new displacement happening,” Elisabeth Haslund, UNHCR representative for Ukraine, told The Independent. “After three years of full-scale invasion, and 11 years since the war began in the east, the humanitarian situation in Ukraine is dire. Millions of people have been forced to flee their homes, and need humanitarian support.”

The majority of Ukrainians are living across Europe, with the most in Germany (1.2 million), Poland (1 million), and Czech Republic (390,000).

The United Kingdom has around 254,000 Ukrainian refugees living in the country as of December.

Over half (52 per cent) of refugees have gone back to Ukraine at least once over the past three-year period; whether that be to visit family, collect belongings, or return for good.

However, most refugees who return to Ukraine intend to stay for just a few weeks, with just 7 per cent intending to return permanently in 2024, down from 19 per cent in 2023.

Within Ukraine itself, a further 4 million people are internally displaced according to UNHCR records. These are people who were driven from their own homes due to the war but remain within the country.

The financial burden for both sides

In a press conference last week, President Zelensky said the war so far had cost Ukraine $320bn (£253bn); the majority of which ($200bn) was shouldered by his country.

The cost of Russia’s invasion to the Kremlin is unknown, but one year ago the Pentagon estimated that the war had already cost Moscow up to $211bn.

Estimates of the scale of destruction in Ukraine vary widely, but ACLED’s database records around 5,500 events which explicitly mention damage to residential properties, schools, healthcare facilities and energy infrastructure.

In 2021, before the war, Ukraine’s gross domestic product (GDP) was valued at around $199.8bn, according to the World Bank.

In 2022, this dropped by around 30 per cent; and in 2024, Ukraine’s GDP is still only estimated to be around 78 per cent of its pre-war levels, according to Ukraine’s Centre for Economic Strategy (CES). Inflation also continues to increase across all sectors of the economy, except clothing and footwear, with some of the highest price rises in utilities and rent.

In Russia, GDP grew by 3.6 per cent in 2023, estimated at $2 trillion by the World Bank, and by approximately 4 per cent in 2024.

Moscow has leaned heavily into oil and gas exports, which hit record-level revenues despite sanctions from Europe and the US.

Yet financial figures from Russia can be obscure, and inflation is still high, at 9.9 per cent year-on-year, with a staggering key interest rate of 21 per cent.

What’s more, defence spending eats up 40 per cent of the Russian government’s expenditure, according to the Carnegie Eurasia Center, and over 8 per cent of its GDP.

Russia spent an estimated $140.5bn on defence in 2024, according to analysis by the Center of European Policy Analysis.

These sky-high sums are the highest since the Cold War, and are primarily funnelled into homegrown arms production and military salaries, according to the Carnegie Institute.

What has Putin taken? The ongoing fight for territory

In March 2022, in the early weeks of the war, Russia tried and failed to capture Ukraine’s capital city of Kyiv. Three years on, in addition to Crimea, Moscow has claimed control of Zaporizhzhia, Donetsk, southern Kherson and Luhansk, with incursions into Kharkiv.

Russia currently occupies around 111,339 square kilometres of Ukrainian territory, according to The Institute for War (ISW) as of 19 February this year, while Ukrainian forces have liberated an estimated 71,938 square kilometres of Ukrainian territory since the conflict began.

Conflict is still occurring daily along the Ukraine front line, over 1,000km long. Recently this has been concentrated on the eastern front line; in 2024 alone, Russia gained thousands of kilometres of territory in the Donetsk region.

Around 200 miles to the northeast, Ukrainian troops have fought to hold onto a sliver of Russian territory in the border region of Kursk.

Approximately 4,200 square kilometres was captured by Russia in 2024 overall, according to the ISW, which has tracked the war in Ukraine since the full-scale invasion was launched.

The significance of the continued control of Kursk remains to be seen, but Mr Trump’s delegation has been clear that territorial concessions will have to be made by both sides.

Inside the conflict: increasing drone strikes

ACLED has researched and collected data on incidents of violence since the February 2022 invasion.

Throughout constant peaks and troughs, the number of conflict events have remained consistently high over each week of the war.

There have been over 146,000 instances of political violence recorded in Ukraine since the start of the war, according to ACLED’s data.

This includes over 25,600 air/drone strikes, 80,500 recorded instances of artillery, shelling and missile strikes, and 36,100 battle events.

At least 95 per cent of air and drone strikes were carried out by Russian actors against Ukraine, say ACLED.

The data is collected from a variety of sources weekly since 2018, and not independently verified.

In the past week alone (between February 8 and 14), ACLED recorded 1,150 conflict events in Ukraine, a third of which were battles and two-thirds of which were remote violence (artillery strikes and drones).

The vast majority of these recent conflict events are concentrated in areas along the front line, with the most man-to-man combat occurring in the Donetsk, Luhansk and Kharkiv regions where Russia has been making gains.

Energy infrastructure in Ukraine has been targeted by Russian attacks, leading to a 65 per cent loss of energy generation capacity, according to UNHCR, with the latest attacks just last week on gas infrastructure in Kharkiv.

The resulting energy crisis has led to inconsistent access to water, electricity and heating, including wider infrastructure needs – with the UNHCR predicting that 12.7 million people in Ukraine will need humanitarian assistance this year.

On the ground: troop numbers and recruitment problems

Ukraine’s army currently has around 880,000 personnel, President Zelensky said on 15 January.

Russia’s army was last estimated at 1.5 million people, according to orders to increase troop numbers from President Putin in September. President Zelensky said in January that 600,000 Russian troops are in Ukraine.

More than 10,000 North Korean troops have been sent to aid Putin’s invasion effort, with reports of some 140,000 to 180,000 convicted criminals being recruited to join the army as of January this year. Russia’s prison occupancy numbers have been slashed in half as a result, according to Ukraine’s Foreign Intelligence Service.

The cost of recruiting alone has amounted to around $16bn to $23bn for Russia, according to the Carnegie Institute.

In Ukraine, the military is turning to the younger 18- to 25-year-olds who are exempt from conscription, developing financial incentives to try to attract more numbers. The current age of mandatory conscription in Ukraine is for men aged 25 to 60, lowered from 27 years old last April.

Ukraine has offered prisoners the chance to be released on parole and join the military since a mobilisation bill was approved in June, with an estimated 27,000 prisoners eligible under certain conditions.

The world reacts: the cost of sanctions

It is difficult to estimate the impact that global sanctions have had on Russia and Russian actors.

Thousands of sanctions against Russia have been implemented by the EU, Canada, Australia, and Japan, with the United States leading the pack.

In the UK alone, 1,733 individuals and 382 entities are subject to sanctions as of January this year.

This has led to £22.7bn of Russian assets frozen in the UK, with oligarchs and banks representing a further £147bn of combined net worth under sanctions, according to the government.

The cost of international support: but how long for?

Over three years, at least 42 countries worldwide have allocated aid for Ukraine worth €267bn.

The majority of this aid comes in the form of military support, according to analysis from the Kiel Institute for the World Economy (IFW), including weaponry, equipment and training.

Military aid from Europe overall (€62bn) is on a par with that from the United States (€64bn), between February 2022 and December 2024.

Yet European countries have delivered significantly more funds (€70bn) for humanitarian and financial aid, than the US (€50bn), according to the IFW.

Over the past three years the UK has committed £12.8bn for Ukraine, according to government figures in January, 61 per cent of which was for military aid.

The IFW’s aid database attempts to count only aid allocations, not commitments, as some commitments are not delivered, or can be double counted.

It is important to note that funding commitments from various countries do not necessarily amount to the value of aid received.

For example, in an interview with Lex Fridman released in January, President Zelensky claimed that Ukraine had not yet received half of the $177bn the US had claimed to allocate.

Mr Trump has claimed the US has given $350bn in aid to Ukraine, a figure undercut by both President Zelensky and independent estimates.

Given the president’s recent criticism of Mr Zelensky, and his preoccupation with the bottom line, how much longer the US will continue to support Ukraine financially remains to be seen.